Jordanian Dirt

Jordanian Dirt

I am working on an essay about I book I read a few months ago, entitled The Map of Salt and Stars, by Zeyn Joukhadar (2018). The working title of my essay is “Syrian Dirt,” because I am so struck by the parallels between Map and Jean Cummins’ notorious novel, American Dirt (2019), which was crucified for ‘cultural appropriation.’

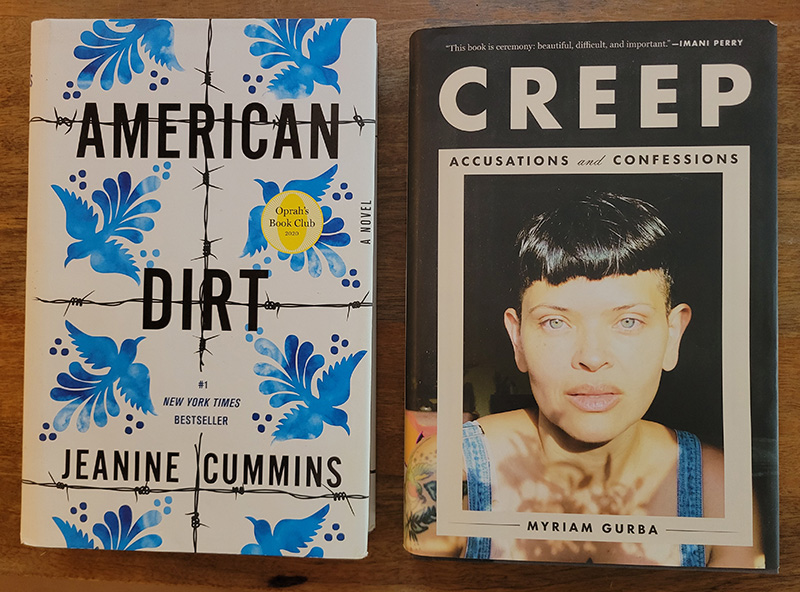

Cummins crashed into the eyewall of the cultural sensitivity storm: she got critically dismembered. “Pendeja, You Ain’t Steinbeck,” is the title of Miriam Gurba’s nasty essay (sort of) contextualizing her own (rejected) review of Dirt, which seems to have inaugurated this shitstorm. Setting aside the ad feminam attacks on Cummins’ character and intent (and ethnicity), Gurba criticizes her for –

- appropriating the work of famous Spanish language writers

- whitewashing them to make them “palatable” to readers in the U.S.

- “repackaging them for mass racially ‘color blind’ consumption”

- stereotyping Mexicans

- not having a sufficiently Mexican sensibility

- having messianic aspirations.[1]

As critic Pamela Paul wrote, “others quickly jumped on board and a social media rampage ensued, widening into the broader media… Cummins’ motives and reputation were smeared; the novel, eviscerated.”[2] It still sold millions of copies.

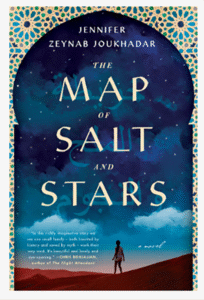

If you haven’t caught wind of any of this, you will have to take my word for it that the frontal attack on American Dirt caused an uproar, an earthquake in American publishing. An uproar that is still the centerpiece for discussion of ‘cultural appropriation’ in Slate and NYT, among other forums, seven years later.[3] What compelled me in 2025 to scour the reviews and profiles of American Dirt, Cummins, Joukhadar, and Map, is the fact that Joukhadar escaped even a glancing blow from the same critique Cummins endured. She (for they were Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar when she first published Map) won prizes, received syrupy reviews and praise for “a wise, vibrantly told story”[4] that “perfectly aligns with the cultural moment.”[5] Map is even – no lie – compared to The Grapes of Wrath, as was American Dirt, rather famously.

And yet Joukhader blows it again and again on points of language, culture, and even simple, empirical landscape.

Like American Dirt, The Map of Salt and Stars follows a disaster-struck family of migrants in search of a safe place to land. In Map Nour, her two sisters, her Mama and a male family friend leave their village in 2011, at the outset of the Syrian civil war, heading for Jordan and beyond. The novel tacks back and forth between 2011 and a richly imagined medieval tale which eventually dovetails with their flight across the MENA region. My finished essay will cover Joukhader’s cultural gaffes as well, but for this blog I’m going to stick to the Jordanian landscape, because that’s my thing, at least here.

I probably enjoyed the well-told medieval yarn because I don’t know as much about the period or the landscape as it was then. But from 2004-2014 my day job was Jordan’s landscapes. In 2011 I was just coming off a three-year stint as the Director of Research & Design for Jordan’s Royal Botanic Garden (less grand than it sounds) during which I drove and walked all over Jordan surveying vegetation and habitats. So, to start, here is a home truth: there are no linden trees in Jordan. Lindens are trees of temperate climates (cf. the famous street named Unter den Lindens, in Vienna, ahem). They don’t grow in the arid Mediterranean world.

Linden leaf – https://freecutout.com/linden-leaf-2/

And yet linden trees are perhaps the most salient motif in Joukhadar’s description of Nour’s time in the poorest industrial suburbs of Amman. Joukhadar waxes eloquent (waxing eloquent is big in Map) about the lindens. They mention the lindens six times in twenty-seven pages. I’m guessing, based on leaf shape, that Joukhadar is remembering a poplar. There are poplars all over the place – the “black poplar” (Populus nigra), found across Eurasia, is used as a street tree throughout Jordan.[6] They are beloved. Here’s the weird thing: any Jordanian can tell you the Arabic name for poplar: hour – حور. Why didn’t Joukhadar (who makes conspicuous claims to Arab identity) just ask? look it up?

Joukhader narrates the family’s flight from Amman south to `Aqaba, on the Red Sea. They describe the “red sandstone and pebbles, big top-hatted cliffs” on the way out of the city (153). They are remembering some other place. There are no cliffs on the way out of Amman. The Desert Highway the family is traveling is rolling, conspicuously barren steppe for another 75 miles.

The Hejaz Railway, western central Jordan The point here is not the train, it’s the landscape background. The Desert Highway runs more or less parallel to the tracks. I can’t find any of my own images of central Jordan, along the Desert Highway, because… there’s not much reason to take a picture unless there’s a train in it. Def no cliffs. Very little red. (photo credit: http://www.nigeltout.com/html/qatrana-towards-amman–11-9-00.html )

“Three hours” south of Amman Nour gets out near tall, red cliffs to pee (154). She is probably at Ras al-Naqab, where the road drops steeply, spectacularly, out of the highlands towards Wadi Rum. Indeed on the next page she notes the sign for the `Aqaba/Ma’an/Wadi Musa junction. She describes her view: Way out, the Gulf of `Aqaba glistens like frog skin, the pinky finger of the Red Sea.

The view toward `Aqaba from Ras an-Naqab (photocredit: https://nabataea.net/travel/other_me_railroads/ras-al-naqab/)

Nope. Maybe on Google Earth?

The Red Sea is still 45 miles away as the crow flies, below some serious mountains indeed. She won’t be able to see the Red Sea until she rounds the last curve out of the steep mountain pass out of Wadi al-Yutum onto the alluvial plane, 46 road-miles south and west.

Trust me, there’s more. Palms on windswept arid steppe, acacias where they aren’t.

It feels very much like Joukhader did a whirlwind tour of Jordan and tried to reconstruct the place from their notes and pictures, but they got all mixed up. The prose is lyrical, and I suspect they just liked the word ‘linden.’ Maybe, on their one-week tour of Jordan they pressed a leaf in their journal and later looked it up on PlantNet. The ‘frog skin’ simile is definitely pretty (despite jarring ‘pinky finger’ metaphor situation), but it does seem like Joukhader cares more for lyricism than the ground facts. Cummins’ fieldwork in Mexico was extensive, but she was lambasted for ‘errors’ much less specific than the examples here.

A book is primarily an object. Its cover is meant to supply key information. Map’s front is framed in an Islamic motif, and the Arabic for the title ( خريطة الملح والنجوم ) hovers dimly behind the English. On the back, next to the author photo, we read:

Zeyn Joukhadar is a Syrian American author and a member of the Radius of Arab American Writers (RAWI) and of American Mensa. Joukhadar is … a 2019 artist in residence at the Arab American National Museum.

In a promotional video for Map, Joukhadar positions herself as a Arab-American/ Syrian American/ Syrian diaspora fifteen times in seventeen minutes.[7]

These are strong moves to identify as Syrian, to establish their authority to narrate a story of Syrian migrants. But identity is not the same as culture. Identity alone is not a qualification to narrate culture – much less landscape.

Both Cummins and Joukhader seem well-intentioned, even naively so. They both want to raise awareness about displaced peoples. They both want to encourage discussion about the borders their characters cross. When Cummins was asked in one interview the one thing she hoped every reader would take away from American Dirt, she replied, “Migrants are human beings. They don’t need our pity or contempt. They deserve fundamental human empathy. They are LIKE US.”[8] In the Simon & Schuster interview Joukhadar says, “—maybe [readers] can read this book and feel a bit like, wow, these people[9] are really not so different from me at all.”[10]

As an American woman currently working on a novel which voices Jordanians, including men, I am invested in this conversation. My own heritage-mix doesn’t include Arabs (uh-oh). I have, however, lived and worked and loved and partnered and befriended with Jordanians for over thirty years, mostly with men, so I feel comfortable speaking that voice. This novel (The Servant of Dreams) also involves white American archaeologists, including men, and I am not a white American (or male) archaeologist. The cast involves a millennial American woman, and I actually feel more confident with the Jordanian male voice than hers.

The irony is, I pretty much hate the way the whole discussion of cultural representation has been framed. Every time we describe another person, a family, a place – never mind a culture, religion, language – we describe a culture not our own. I wanted to cheer when I read Gabrielle Zevin’s takedown of the whole construction of ‘cultural appropriation:’

The alternative to appropriation is a world where white European people make art about white European people, with only white European references in it. Swap African or Asian or Latin or whatever culture you want for European. A world where everyone is blind and deaf to any culture or experience that is not their own. I hate that world, don’t you?[11]

To quote Pamela Paul, “It wasn’t just that Gurba despised the book. She insisted that the author had no right to write it.” Later, Paul quotes Guillermo Arriaga as saying, “I think it’s completely valid to write whatever you want on whatever subject you want.” If these two form a continuum, I certainly land closer on that line to Arriaga than to Gurba. But if your stated aim is to represent a particular place and time and people, ostensibly because you care so much for them, getting it right would seem to be the responsible thing to do. I am obviously not alone in thinking that the misrepresentation of cultures, people, places can perpetrate very real harm. And I wonder how differently Joukhadar might have fared in critical circles if the strong claim to be Syrian Arab had not been made, if she’d been passing as white. If she had gotten a seven-figure advance.

So, yeah – Joukhadar can write whatever they want about Syrian migrants, Muslims, Jordan, whatever. Of course. But once the claim to Syrian identity is made, the Mensa card played, and the purpose to represent ‘these people,’ the author also dons a cloak of responsibility to get it right. At least make a good faith effort. The Map of Salt and Stars bears a faint fragrance of intellectual arrogance. Corresponding with a Jordanian friend about all of this, he wrote, “[they’re] just counting on the same old stereotypes: backward Arabs, ignorant Americans.”[12] I think he nailed it. It seems to me that Joukhadar assumes that no Jordanian will ever read the book, and every American is too ignorant to catch them out, which is disrespectful to everyone involved. In the end, The Map of Salt and Stars is just more American dirt.

_____

[1] Myriam Gurba, Creep, 253-261. The thing is, these fair/intriguing points might have yielded an interesting, and even powerful essay, if they hadn’t been buried in rambling nastiness.

[2] Pamela Paul, ‘The Long Shadow of American Dirt,’ NYT, Jan 26, 2023

[3] In May 2025 I read Laura Miller’s Slate review of Jean Cummins’ new novel. Right about the same time, in connection with the NYT review of same, I read Paul’s 2023 article.

[4] Library Journal, April 1, 2018 www.libraryjournal.com

[5] The Providence Journal; Sandra Cisneros wrote of American Dirt, “This is the international story of our times.”

[6] There are also, here and there, Euphrates poplar (Populus euphratica), but this would be really unlikely in East Amman. But anyway – poplars! Ashkenazi, et al, ‘Poplar trees in Israel’s Desert Regions: Relicts of Roman and Byzantine settlement. Journal of Arid Environments 193 (2021). https://www.academia.edu/50042506/Poplar_trees_in_Israels_desert_regions_Relicts_of_Roman_and_Byzantine_settlement_2021_JOURNAL_OF_ARID_ENVIRONMENTS

[7] You Tube: Simon & Schuster, “Meet Summer 2018 Preview Speaker Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar, Author of The Map of Salt and Stars.” April 16, 2018.

[8] BookBrowse interview with Jeanine Cummins. https://www.bookbrowse.com/author_interviews/full/index.cfm/author_number/3268/jeanine-cummins (accessed 21 Nov 2025)

[9] Cummins got ripped by Gurba for referring to migrants as ‘these people” (Creep 254). I am wondering how the Gurba:these people / Joukhader:these people/ Cummins:these people syllogism works, or doesn’t. Is Gurba a migrant? Or is just being Mexican-(Polish)-American enough to write about migrants? Frankly I’m lost (probably because I [pass as] white).

[10] YouTube Simon & Schuster – 13:20

[11] Gabrielle Zevins, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow. Knopf 2023 (78).

More irony: Gurba is quoted in a 2016 interview saying, “Identity has two I’s in it, just like most faces have two eyes. That’s because identity is an “I” statement. It is who I am. It is who people think I am. Feeling weird about your identity is okay. Feeling unsure about your identity is okay. Arguing about your identity is okay. Protecting your identity is okay. Changing your identity is okay. Our identity changes with time. Have fun with your identity. Let your identity play with other identities. Try on new identities. Fantasize about all the identities.” (https://molaa.org/who-are-you-myriam-gurba).

If only, and at your peril from people like Gurba.

[12] Thanks to Zaki al-Nazli for ongoing conversation.

_____

Title image of poplar leaf, photo credit: https://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/trees-woods-and-wildlife/british-trees/a-z-of-british-trees/black-poplar/